Demystifying some of the language around buying true, free ranging pastured pork that’s of sound quality, ethics, and breeding.

I spend a lot of time talking with farmers and customers about pork—how it’s raised, and why it tastes the way it does. This piece is here to unpack some of the language we see on labels every day, so you can make informed, confident choices.

The label looks good. There’s a few iconic farm instalments like a barn, a windmill, a group of happy pink pigs in a paddock. An up-close, seems-to-be-smiling, snout. Or maybe it’s the logo – a happy looking pink pig silhouetted against an idyllic farm sunset. There’ll be tags, too. Buzzwords like ‘free range’ and ‘sow stall free’ and ‘happy pigs’. The colours will be green, white, and pink.

Happy, happy, happy.

You’ll quickly notice a pattern. Idyllic imagery designed to evoke trust and comfort: visuals carefully chosen to create a sense of natural, welfare-friendly farming, – design elements that are not accidental—they are marketing tools intended to reinforce the idea of “happy pigs” and ethical farming practices.

These visual and written cues are designed to build trust and suggest high welfare standards. However, they do not always tell the full story about how pigs are raised, what they eat, or how they are processed. Understanding the language and imagery used on labels is the first step in making informed decisions about the pork you buy.

Globally, pigs popularly considered ‘pink’ are officially recognized as ‘white’, and are generally the Yorkshire, (‘Large White’) breed, the breed that provides the cornerstone for most commercial pork operations. The white pigs of today are bred in large numbers for supermarkets, general butcher shops and small retail franchise chains. They’re also used in fast food joints and budget conscious or low turnover restaurants and cafes.

The commercial industry began favouring white breeds around 40 years ago, with numbers increasing as consumers demanded the more fashionable cuts of the day – think belly, leg roast, lean loin chops – leaving the rest of the pig to be discarded. This raised the overall cost of the product and put pressure on growers to grow more, faster.

There’s nothing wrong with these pigs, as such, it’s really more about what they represent – how they have may been sired, for instance; or their genetic background and DNA and how it’s been altered to suit a market that wants individualised portions of cheap pork in large quantities. It’s about the term ‘free range’ and what it really does (and doesn’t) represent. It’s also about terminology.

White pigs, because of their pale colouration, require a lot of shelter in order to avoid sunburn. Now, a pig doesn’t know if they are getting sunburned. So, they’re usually ‘sheltered’ from the elements by spending their days group housed (or loose house) in roofed enclosures, often on concrete pads. It is here that they are ‘free to range’.

So what are your options?

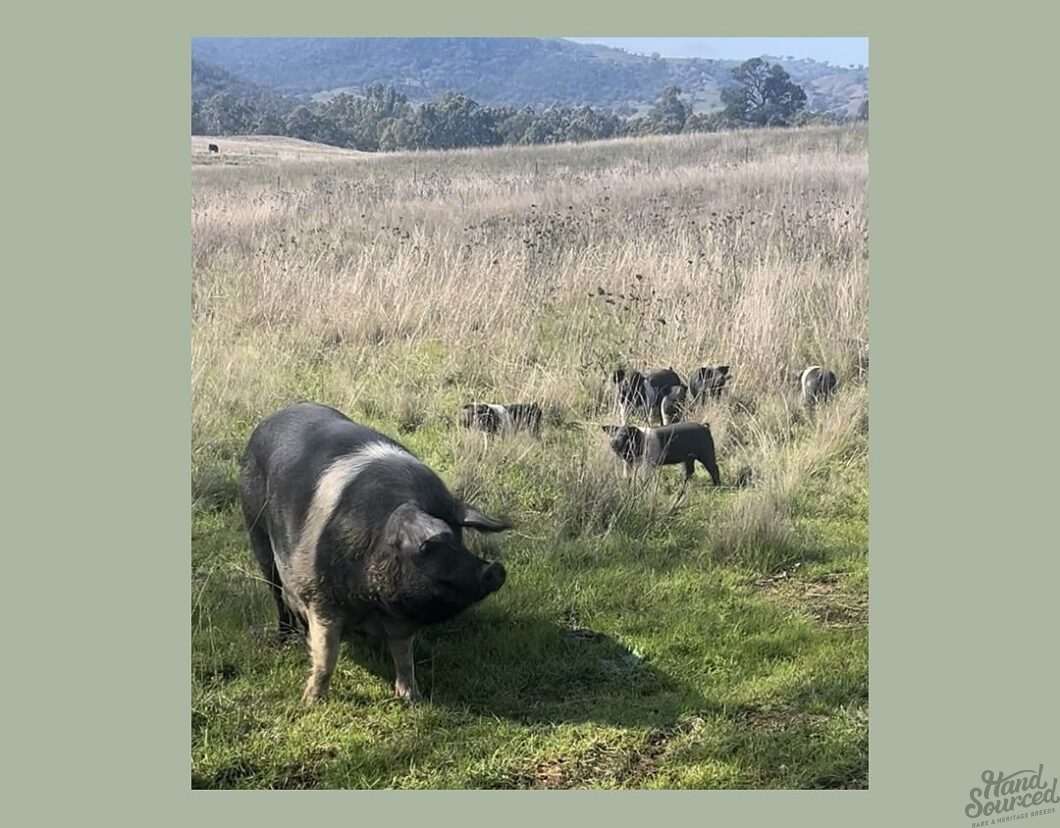

The Wessex Saddleback and the English Blacks and the Berkshire Blacks are each a very fat breed, a true, slow growing animal that sport black hairs providing natural resistance to harsh elements and sunburn. This natural resistance means they can ‘free range’ in the truest sense of the word – paddock or bush, field or dam, to wallow or graze.

However, it’s this idyllic life that led to their declining popularity. Domestic consumers, once presented with a pink-skinned pork roast, began demanding their Sunday roast without the errant black whisker. Health authorities convinced us that lean pork (and other lean meats) were the only way to go, increasing – you guessed it, that cycle of consumer demand, cost of product and pressure to grow more, faster.

Slow growing animals, yielding higher fat content, require manual attention to carefully butcher, remove hairs and trim organ fat. But fat means flavour and manual labour means money and our once flavourful, slow growing breeds became rare simply to meet the needs of a commercial industry driven to produce faster growing, leaner, cheaper meat.

And commercial industry means confined or intensive farming conditions, a system in which faster growing, often hybrid white pigs thrive and heritage lines to not.

It’s a matter of taste.

We all agree, fat is flavour. We are also now rediscovering the true health benefits of animal fats. Flavour also comes from well used (and well rested) muscle tissue, and in commercial farms where pigs are unable to roam, wallow or explore, muscle tone and texture are compromised. To combat this, commercial system uses a growth promoter called ‘Paylean’ alongside specific hormones designed to force a faster growing hog that lays down muscle, but not fat.

The wonderful flavour of a true, free ranging product reflects both a natural, slow growth rate and the environment in which the pig lives., with the best flavours coming from sustainable, pasture raised systems. No stress, no cages, no enforced shelters.

Free range, sow stall free, what does it mean?

Sow Stalls (sometimes called farrowing crates) are used to confine individual sows in intensive pig production. This is the most common method of pig production and the yield of pork that is provided to ethnic butcheries and fast food restaurants. These stalls are very restrictive and do not allow free and natural movement by the sow. All she can do is stand up or lie down. She cannot turn around.

Farrowing crates allow the producer to have easy access and control of the sow during the birth and while she is raising her young, restricting the movement of the sow to prevent piglets from being laid on by their mother.

Sow stall free pigs are grown under the usual intensive, factory farmed conditions, but sows are group housed (also called ‘loose housing’) in sheds. All major supermarket pork is raised in this manner. Supermarket ‘stall free’ pork comes from younger animals, far smaller than the breeder ‘parent’ pigs (which are kept specifically for this purpose). These youngsters only grow to around 75kg and are raised in small indoor pens on concrete in sheds or ‘eco-shelters’.

Free Range: Smaller, ‘boutique style’ farms that still grow white pigs often practice group or loose housing known as free range. Loose housing is a broad term which encompasses a range of alternatives to sow stalls. Critically, any loose housing must provide a sow with freedom of movement – she must be able to turn around and extend her limbs. It does not mean she allowed to range free outside. Most loose housing systems involve keeping the sows in groups, although individual pens are permitted, as long as they allow freedom of movement.

Legislation that allows the practice of keeping sows in stalls, and allows the sow to be kept in farrowing crates for up to 6 weeks of each lactation (each time she gives birth – twice a year on average) Refer here for the Code of Practice.

Boutique pork: Sow stall free ‘Free Ranging’ in loose housing

So what about those buzzwords?

True, organic pork is as rare as hen’s teeth. The legal interpretation of the term ‘organic meat’ requires a certification. This guarantees that the consumer is buying a product that is 100% free of all residue of chemicals, pesticides, germicides, insecticides, artificial fertilizers; (organophosphates and organochlorides), heavy metals and restricted inputs.

When you buy produce labelled with “grass-fed”, “sustainably farmed”, “pasture raised” and “clean and green”, you are being sold something that’s not legislatively certified. Therefore, you could still be consuming heavy metals, chemical residues and artificial fertilisers and other contaminants. This is why it’s important to know your farm, or your farmer, and where your product comes from.

What you can look for

Pastured pork is not ‘grass fed’, in the true sense of term, as pigs cannot survive on grass alone. Rather, pigs are omnivores and get much of their nutritional needs from the soil, small amounts of grass, and supplementary nutritionally balanced feed. ‘Pastured’ free range pigs have access to grazing, live in open paddocks with plenty of room, no feedlots and no overcrowding and definitely no indoor confinement. Raising pigs on pasture means sows live their entire lives outdoors and give birth outside while being provided protection from the elements and predators.

Regenerative pork is produced using farming methods that restore soil health, increase biodiversity, and prioritize animal welfare, often involving pasture-raised or forested, free-roaming pigs. Unlike industrial models, these practices avoid confinement, relying on natural foraging and rotational grazing to improve ecosystems, producing nutrient-dense, chemical-free meat.

Key aspects of regenerative and pastured pork production include:

- Environmental Impact: Methods focus on building healthy soil, fostering ecological restoration, and avoiding synthetic inputs.

- Animal Welfare: Pigs are raised in open, natural environments (pasture or forest) allowing them to forage and behave naturally, typically without antibiotics or hormones.

- Meat Quality: Often sourced from rare or heritage breeds (like Wessex and Berkshire) that are slow-grown, resulting in richer, higher-quality meat compared to conventional factory-farmed pork.

You’ll rarely find this meat in your local supermarket, home delivery service, or butchers that buy in boxed meats (boxes of cuts versus butchering their own carcasses)

If you’d like to know more about how buying ‘cheap meat’ affects more than you’re sensibilities, here’s a great listen for those interested in how our meat supply chain is affecting our farmers in Australia.

http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/blueprintforliving/the-true-cost-of-cheap-meat/9224506

Choosing better pork isn’t about perfection—it’s about transparency, animal welfare, and supporting farmers who care for land and livestock. Small choices add up.

Leave a Reply